Story of cities #32: Jane Jacobs v Robert Moses, battle of New York's urban titans | Cities | The Guardian

Jane Jacobs is a veteran of Massive Small thinking. Not only does she reimagine the city as a humane habitat; she has demonstrated the power of collective to take on existing power structures and thinking paradigms. What started as a personal stance, changed how we think about urban development, globally. It begins with a response to a very local challenge.

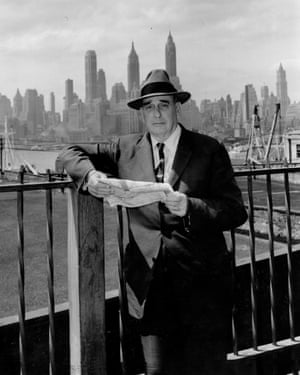

In 1961, Bennett Cerf, one of the founders of the publishing firm Random House, sent a copy of a new book by Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of American Cities, to the legendary city planner Robert Moses. Moses’s reply was curt:

Dear Bennett,I am returning the book you sent me. Aside from the fact that it is intemperate and inaccurate, it is also libelous. I call your attention, for example, to page 131. Sell this junk to someone else.Cordially, Robert Moses

This was no ordinary demurral over a book’s merits. It was a salvo in a struggle between a man who had amassed vast bureaucratic powers and remade New York with expressways, parks and housing towers, and the woman who assembled neighbours and public opinion to stop him when he set his sights on the evisceration of a swath of lower Manhattan.

Moses was an avatar of the early 20th-century vision that the only salvation of cities was the large-scale destruction of their existing features, and Jacobs an exemplar of another, which maintained that the future of cities rested on preserving exactly those qualities. Jacobs’ book was the most powerful retort to Moses’s mode of thinking, and her actions a resounding retort to his mode of operating.

The struggles between Jacobs and Moses loom large in the popular consciousness. The subject of books by Roberta Brandes-Gratz and Anthony Flint, they now feature in what is surely the world’s first opera about an urban planning dispute, A Marvelous Order, which premiered last month.

The only hazard to this libretto is that their conflict, which has become an iconic representation of the tension between top-down and organic notions of urbanism, was one in which most contact was indirect. In fact they encountered each other in person only once. Moses’s sneering dismissal of Jacobs’s book was one of very few direct acknowledgements of her existence.

This is fitting since both worked through realms of indirect influence and power: Moses within the byzantine and barely accountable tangle of New York’s public authority powers; Jacobs in the inherently decentralised world of community organising and writings about urbanism. But however indirect the sparring, there’s no doubt who prevailed in the end.

‘Immense behind-the-scenes influence’

Despite never winning a single election, Robert Moses reigned over a set of principalities that would rival a Habsburg monarch. At his peak he held 12 offices, the most prominent being the New York city parks commissioner, state parks council head, and chairman of the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority. The latter, created in 1933 to oversee construction of the set of bridges connecting Manhattan, the Bronx and Queens, was pivotal, providing Moses with a steady stream of revenue that he leveraged into countless other construction projects.

As Robert Caro wrote in his epochal tome The Power Broker, “Moses … displayed a genius for using the wealth of his public authorities to unite behind his aims banks, labor unions, contractors, bond underwriters, insurance firms, the great retail stores, real estate manipulators – all the forces which enjoy immense behind-the-scenes political influence in New York.”

Moses’s early construction was largely confined to Long Island: he steadily knit his spider’s web of roads nearer the heart of the city, bulldozing increasingly dense urban fabric and eventually setting his sights on Washington Square Park, the historic centre of Greenwich Village.

Washington Square Park anchored the Village, offering 10 acres of green space to a steadily changing set of neighbours, from Edith Wharton to Bob Dylan. In 1880, Henry James wrote in Washington Square of its “rural and accessible appearance” – a quality that had not entirely dimmed by the 1950s. Moses, however, upon looking at the park, was convinced that the amenity it most sorely lacked was a four-lane road through its centre.

One neighbourhood resident, Jane Jacobs, received a flyer from the Committee to Save Washington Square Park in 1955, providing notice of the proposal to extend Manhattan’s 5th Avenue through the park. Jacobs, born in the small city of Scranton, Pennsylvania, had arrived in the neighbourhood in the 1930s, holding a variety of writing jobs culminating in work for the prominent publication Architectural Forum.

News of the proposed roadway provoked alarm. In a letter to the city’s mayor, Jacobs wrote: “It is very discouraging to do our best to make the city more habitable and then to learn that the city is thinking up schemes to make it uninhabitable.” Moses’s previous road plans had an unerring tendency to become reality. Jacobs set about ensuring that this one didn’t.

She rapidly took on the roles of both strategist and media and community liaison with the park’s committee, displaying a great skill for community organising – enlisting supporters both small and large, from local children to prominent neighbourhood residents such as Eleanor Roosevelt.

Washington Square Park in 2016. Photograph: Ali Smith for the Guardian

Jacobs cultivated the media in all its forms, garnering the support of independent press such as the nascent Village Voice. Nor were traditional levers of power neglected: the support of Carmine DeSapio, New York secretary of state, Democratic machine politician and Village resident, proved very helpful. The Board of Estimate (a city body controlling land use decisions) was prevailed upon to drop the plan.

It was amid this process that Jacobs saw Moses for the only time, as she reported to James Howard Kunstler in a Metropolis Magazine interview:

I saw him only once, at a hearing about the road through Washington Square, which was to be an entrance ramp to the Lower Manhattan Expressway. He was there briefly to speak his piece. But nobody was told that at the time.None of us had spoken yet because they always had the officials speak first and then they would go away and they wouldn’t listen to the people. Anyway, he stood up there gripping the railing, and he was furious at the effrontery of this, and I guess he could already see that his plan was in danger. Because he was saying: ‘There is nobody against this – NOBODY, NOBODY, NOBODY but a bunch of … a bunch of MOTHERS!’ And then he stomped out.”

The official 1936 opening of the Triborough Bridge, a construction project which helped consolidate Robert Moses’s political power. Photograph: AP

Jacobs continued her struggle against urban renewal by articulating a positive vision of the “teeming city” in a 1958 article for Fortune magazine – which led to the commission of her masterwork, The Death and Life of American Cities.

The city is like an insane asylum run by the most far-out inmatesJane Jacobs

This broadside against the prevailing scientific rationalism of urban planning extolled diversities of usage, old buildings and the organic structures of cities: “Why have cities not, long since, been identified, understood and treated as problems of organised complexity?” It was a powerful call in an era in which any such complexity was the very thing that planners were looking to organise out of existence.

Another such effort arose about a month after Jacobs had finished her manuscript. The city’s Housing and Redevelopment Board was pursuing a study intended to classify a large area of Greenwich Village south of Washington Square Park as “blighted”, in order to enable large-scale redevelopment. Moses was not personally responsible but his associates headed the effort. Jacobs soon became co-chair of a Committee to Save the West Village, devising a new set of efforts to derail the flattening of her neighbourhood.

Jane Jacobs at a press conference in Greenwich Village in 1961. Photograph: Alamy

Moses’s efforts had frequently glided forward thanks to assertions of expert knowledge unavailable to the general public and the skilful manipulation of civic processes. Jacobs fought back on both fronts. The committee conducted their own survey of neighbourhood conditions to rebut the “blighted” designation, collecting ample documentation that the neighbourhood was not, in fact, a slum.

Public hearings on the proposal had not been held, as mandated by law; Jacobs obtained an order from a state judge that they must take place. It soon emerged that the City Planning Commission had already, surreptitiously, designated the area as blighted.

A frequent Moses tactic, aped by the city in these proceedings, was to schedule public hearings at short-notice, to avoid mobilised resistance. But Jacobs had a source at City Hall providing regular tips, and worked to deluge these meetings with opposed citizens.

Additional skulduggery was unearthed. She noticed the same irregular “r” appearing both on press releases from the real estate company charged with redeveloping the area, and on statements from an ostensible community group in support of the redevelopment. The latter was revealed as a front that had vastly misrepresented the scale of the project proposed to neighbourhood residents.

Rising public distaste with the secrecy and collusion at work in the process led to the city’s abandonment of the “blighted” designation, and its plans for redevelopment. By then, however, another, potentially more destructive, threat awaited.

‘A monstrous and useless folly’

The Lower Manhattan Expressway was an effort to tie up the loose ends of local roadways by extending Interstate 78 – all 10 lanes of it – from the Holland Tunnel to the Manhattan and Williamsburg Bridges. The obstacle was the streetscape of SoHo and Little Italy, and the great variety of uses within that the city found dispensable.

“The grand total for proposed demolition was 416 buildings that housed 2,200 families, 365 retail stores, and 480 other commercial establishments,” wrote Anthony Flint in Wrestling with Moses.

Greenwich Village residents protest against Robert Moses’s plans to build the Lower Manhattan Expressway in 1960. Photograph: Alamy

The area was both densely settled and architecturally significant, containing one of the greatest collections of cast-iron architecture in the world. Yet neither factor registered as even slightly consequential initial objections to a fresh new expressway – and one eligible for 90% federal funding as part of the Interstate Highway system.

The expressway had the support of the city, the Regional Plan Association, the American Institute of Architects, the Municipal Art Society, business groups and construction workers’ associations.

Once again, Jacobs set about forging a diverse local coalition to stop it.

An organic network of support was developed, drawing on a diverse set of local residents, Puerto Ricans, Italians, intellectuals, labourers and, rumour has it, even the mafia – united by a common opposition to their homes and businesses becoming a merge lane.

Jacobs’s coalition pursued both short- and long-term tactics, obtaining delays for resident relocation studies while holding frequent rallies – one featuring residents in gas masks, to dramatise the likely increase in pollution – and blanketing any public hearings with opposition. She herself offered frequent quotable barbs, once describing the expressway at a Board of Estimate meeting as a “monstrous and useless folly”.

New York’s SoHo district is still home to some of the world’s most famous cast-iron architecture. Photograph: Michael Pasdzior/Getty Images

The city’s mayor, Robert F Wagner, halted the condemnation proceedings in 1962. But the expressway was a beast that refused to be slain, thanks to continued support from powerful backers – none more powerful than Moses. By 1965, the mayor announced his renewed support, offering a slightly altered plan that submerged parts of the expressway complex, as well as a proposal for some new housing as a sop to relocated residents.

Mayoral challenger John Linsday took up the baton of expressway opposition – yet once elected, he too went about tweaking the proposal in the hopes of making it more palatable. New versions included an 80-foot elevation and an ultra-modern Paul Rudolph proposal for a wrapping of new housing. Multi-lane highways are, however, a difficult dish to make appetising.

The city’s steamroller processes continued. At one public meeting concerning the project, writes Flint, “the microphone faced toward the audience, not the officials the residents were nominally addressing ... suggest[ing] that state officials were just going through the motions.”

“The city is like an insane asylum run by the most far-out inmates,” Jacobs pronounced. She led protesters on to the stage, and the stenographer’s record of the meeting was destroyed. She was arrested and jailed for a night on charges including inciting a riot and criminal mischief, and could have faced years in prison if convicted.

Jacobs eventually determined to leave New York. Her architect husband had obtained a commission in Toronto, and she was eager to take her sons beyond the risk of the draft for Vietnam. She left in 1968 – not in defeat, however, but in victory. The expressway project had lost all steam, and Mayor Lindsay declared it scrapped the following summer.

Moses received his final comeuppance in the same year, undone by the internal manoeuvrings in government that had so elevated him, as Governor Nelson Rockefeller engineered the dissolution of his most lasting fiefdom, the Triborough Bridge Authority. While Jacobs went on to enjoy a distinguished career as author and urbanist, Moses descended into increasing obloquy. He died in 1981, Jacobs in 2006 – one largely reviled, the other venerated.

“And sure enough,” wrote Tom Wolfe in 2007, “over the past 40 years, the rebirth of Lower Manhattan from Chelsea to Tribeca, of northern Brooklyn, of Astoria and Long Island City in Queens, has taken place without razing a single building in the name of ‘urban renewal’, or shooing away a single citizen through ‘eminent domain’.”

Jacobs – one of those common citizens, denigrated at the time as merely a “housewife” – has, perhaps more than any other, offered inspiration to those informed that plans drawn up in the corridors of power will require them to move elsewhere. Simply say “no”.

Does your city have a little-known story that made a major impact on its development? Please share it in the comments below or on Twitter using #storyofcities